Most of the time, our DNA follows the rules. It replicates faithfully, passes down genetic information, and quietly carries out the instructions that make us who we are.

But hidden deep in the genome are tiny rule-breakers: transposable elements, or ‘jumping genes’. These DNA fragments can move around the genome, sometimes landing in places where they disrupt important processes, especially during the earliest, most delicate stages of development.

Scientists are now investigating these jumping genes as genetic accomplices that potentially contribute to infertility, miscarriages, and other reproductive challenges. And researchers like UQ PhD candidate Renee Chu are on the case.

Playing ‘telephone’ with jumping genes

In her Three Minute Thesis presentation, Renee uses a creative metaphor to make the complex science behind her PhD more approachable for a broader audience. She compares DNA replication to a game of ‘Telephone’.

“To win the game, the first player says a message, and it is passed from one player to the next until the last player says the message correctly,” says Renee.

“DNA needs to pass on messages step by step correctly to win the game of life.”

“However, there are some players in this game that don’t follow the rules and pass along the wrong message.”

These players are the jumping genes, which can move randomly around the genome. Renee is studying how these genes behave during the early stages of germ cell development, which is what eventually creates sperm and eggs.

Scientific breakdown: Renee’s research team is looking at a specific type of transposable element: LINE-1 (L1) retrotransposons. They’re using mouse embryonic stem cell models to investigate how L1 expression is controlled, how its mobilisation may impact genome stability during this critical developmental window, and what keeps them in check.

Unfortunately, the gene mutations caused by jumping events don’t give anyone superpowers like in the movies – at least, not that we know of.

Instead, when these genes jump into an area that is important for healthy human function, they can lead to serious health problems. These ‘bad jumps’ have been linked to more than 130 disease cases, including some cancers and neurological disorders.

Renee and her fellow researchers are looking into how and when these jumping genes enter play.

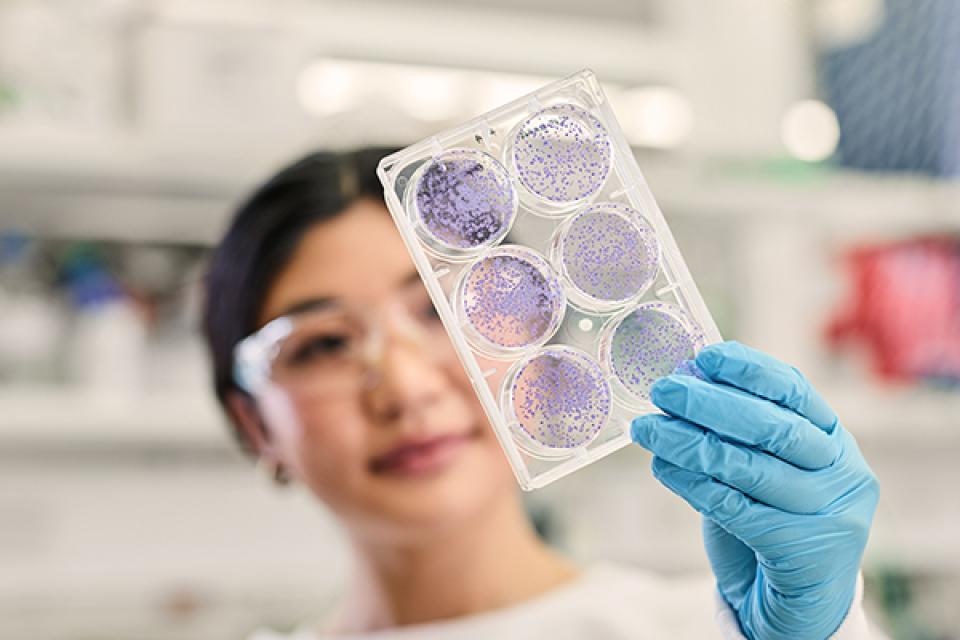

“To study this, we introduce engineered jumping genes into mouse embryonic stem cell models that mimic different stages of early embryonic development,” says Renee.

“What’s cool about these jumping genes is that we can track their activity visually, because as soon as they jump, the cells glow brightly, telling us that they’re interrupting the game.”

Renee’s research suggests that jumping genes may be most active during the earliest stages of embryonic and germ cell development – a critical period when the genome is being reprogrammed and cellular defences are not yet fully in place. This heightened activity could potentially contribute to early developmental disruptions, including:

- infertility issues, which are experienced by 1 in 6 Australian couples

- miscarriages, which occur in at least 15% of confirmed pregnancies.

Renee hopes her research can shed light on any environmental factors that influence the behaviour of jumping genes, as well as potentially discovering defence mechanisms we have to keep them in line. More broadly, she hopes that understanding this process will eventually help with piecing together the bigger picture of genome stability and fertility.

“Hopefully, in the future, only the correct messages are passed on, so in the end, the baby wins ‘Telephone’ and can go on to win the game of life.”

Renee’s collaborative PhD experience

While Renee’s research dives deep into the inner workings of the genome, she’s never had to go it alone.

Her supervisory team spans a variety of specialisations:

- Dr Sandra Richardson, Renee’s principal adviser and the Group Leader of Renee’s research team at the Mater Research Institute

- Dr Stephanie Workman and Dr Nathan Smits, both members of Sandra’s research group

- Dr Adam Ewing, who leads the Translational Bioinformatics Group at the Mater Research Institute

- Professor Josephine Bowles from UQ’s School of Biomedical Sciences.

“Working within a multidisciplinary environment has allowed my project to integrate molecular techniques, computational approaches and developmental biology, providing a more holistic understanding of my research questions,” says Renee.

“This integration has been crucial in addressing complex biological problems that require insights from multiple angles.”

“Collaborating across these fields has broadened my perspective, connected diverse scientific viewpoints, and challenged me to think critically and creatively. These experiences have not only enhanced the quality of my research but also helped me grow into a more adaptable and innovative researcher.”

The opportunity to work with such supportive and inspiring supervisors was a key factor in Renee’s decision to pursue her PhD at UQ.

“As an international student who moved overseas for study, having that mentorship and encouragement was crucial for both my personal and professional development throughout my PhD journey,” she says.

What led Renee to her PhD?

Renee’s always been drawn to understanding the ‘why’ behind things. So, when it came time to choose what to do after her undergraduate studies, research felt like an obvious next step.

“I’ve always been driven by curiosity and a love of learning,” she says.

“Research felt like the most natural extension of that – it’s a space where asking questions is encouraged and finding answers can genuinely contribute to something bigger.”

Her curiosity had always drawn her towards big biological questions. But it was seeing knowledgeable and supportive women in STEM – especially her principal supervisor – that gave her the confidence to fully immerse herself in scientific research.

“Sandy’s example made the path feel more achievable and meaningful,” says Renee.

Renee’s advice for future PhD candidates

For Renee, picking the right research topic and finding the right people to work with was the most important part of starting her PhD.

“Choose a project and supervisor you genuinely connect with – it makes all the difference,” she says.

Ready to embark on your own research journey?

Learn more about UQ’s PhD program and start your application